Erebus, Royal Navy’s Rocket Firing Ship of 1814

There are many great lines included in Francis Scott Key’s song The Star Spangled Banner, our National Anthem. When Key wrote those inspiring verses, he was watching the British attack from the deck of a British man of war, the Tonnant.

Contrary to a popular myth, Key was not a prisoner of the British but rather had gone onto the warship in order to secure the release of a prisoner, one Dr. William Beanes, a prominent surgeon who had been captured at the battle of Bladensburg.

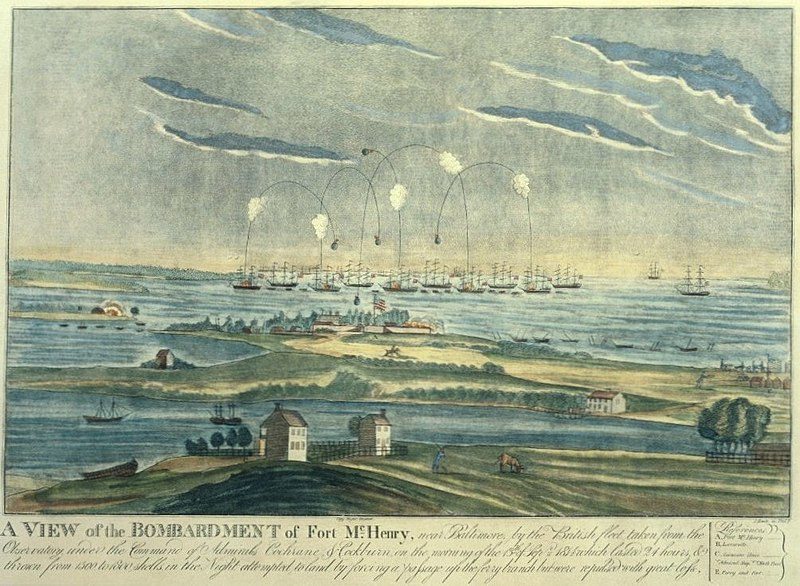

The battle raged through the night, with British warships firing salvo after salvo at Fort McHenry. As dawn was breaking, Key saw the flag flying above the fort and was moved to write those famous verses. Originally titled The Defense of Fort McHenry, it wasn’t until 100 years later that it became our National Anthem.

Amongst those famous verses, we find the phrase “The rocket’s red glare; the bombs bursting in air…” which lit up the scene enough that he could see “That the flag was still there.”

Yet, what were those rockets? What bombs burst in the air?

If Key was transported through time, it would not seem unreasonable for him to have talked about rockets in flight during a war. The modern battlefield has a number of different types of rockets, from the MRLS (multiple rocket launch system) of the artillery to cruise missiles fired from far offshore.

But the technology of the day didn’t include these marvels of modern military power. Cannons were in abundant use, both from the ships and from the fort, but that’s about it… or was it?

Perhaps it would make more sense if we thought of these rockets more like giant fireworks – specifically, like giant pop bottle rockets. They weren’t the kind of rockets that had powerful explosive warheads that could sink a ship or blow up a building; they were mere fireworks.

The Chinese invented these types of rockets, starting back in the early 1200s. They were mostly a terror weapon, flying towards their enemy screeching and billowing smoke. To soldiers and sailors unaccustomed to such weapons, I’m sure they were terrifying indeed.

The ones fired at Fort McHenry were an improved design invented by William Congreve, the son of a British Lieutenant General of the Royal Artillery.

Starting with the Chinese design, young Congreve sought to make it better, hoping to turn what was nothing more than a terror weapon into something that could be used to sink ships. By the time the battle of Fort McHenry happened in 1814, he had spent a decade on the project.

There were several things that made Congreve’s rockets different from the original Chinese ones. To start with, they were larger and heavier with a metal casing.

They came in a variety of sizes, all the way up to one that was 18 inches in diameter! He had experimented with cardboard casings, like the Chinese used, but found them too unreliable and created a metal casing. They also had a longer tail pole, much like a scaled-up version of the sticks we find on pop bottle rockets today.

Through extensive testing, Congreve discovered that 55 degrees was the ideal angle at which to fire the rockets, allowing the greatest range.

Compared to the few hundred feet that the Chinese could get out of their rockets, Congreve was reaching distances of up to 3,000 yards, or more than 1.7 miles. This success was from a combination of making larger rockets and packing the gunpowder tightly to create a more consistent burn rate.

But, no matter what he did, the young inventor couldn’t make a rocket that would fly straight and true. While his rockets did considerably better than the ones he had started with, they never reached a point of being truly reliable.

Another of Congreve’s major innovations was the act of installing warheads onto his rockets. He had both explosive and incendiary warheads available for the various-sized rockets.

The ones that were fired upon Fort McHenry were of the incendiary type, hoping to start a fire within the walls of the fort. Originally designed for use against the wood sailing ships of the day, these rockets, which weighed 32 pounds and were 3.5 inches in diameter, had already been used as a terror weapon in the war to burn down private homes.

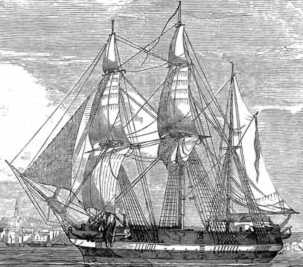

While never fully effective, this project was important enough to the Royal Navy that the rockets fired upon the fort were fired from a ship specially equipped for the task. Erebus, the second rocket-firing ship, had started life as a Royal Navy 18 or 21 gun sloop and had been modified by the removal of her cannon and the installation of “firing racks” for rockets.

These racks, which were below decks and fired through holes in the sides of the hull, much like cannons, allowed for the shooting of 10 rockets out of each side of the ship.

Nevertheless, the Royal Navy’s venture into rocket-powered warfare was unsuccessful. Somewhere between 600 and 700 rockets were fired at the fort during the 25-hour assault, but not one of them accomplished their goal of setting the fort alight. They all fell short and landed in the bay.

This was not as much due to the fault of Erebus and her crew, but rather due to the effectiveness of the artillerymen on shore.

The American gunners were too good at their task and did not give the British vessel a chance of getting close enough to shore to guarantee a hit. For the British, it was an expensive and failed experiment.

Only three people were ever killed by Congreve’s rockets, but they did leave a legacy. Unfortunately for the British, it was not a legacy in their favor. Rather, those rockets were memorialized in Francis Scott Key’s song as he saw the Stars and Stripes lit up by them as the battle drew to a close.

Yet, the rockets were not a total waste. As with many other breakthroughs in military technology, the rough early versions were not all that effective. Yet, it is those ineffective attempts that open the door for greater research and development, which ultimately leads to a new family of weapons.

Had it not been for the inventive curiosity of William Congreve, the MLRS and Tomahawk Cruise Missile, as well as a host of other weapons, might never have been created.