A Mining Company in Australia Blew Up Aboriginal Caves Full of 46,000 Years of History

History recently lost out in favor of industry in Australia, when a 46,000-year-old aboriginal cave was blown up by a mining company.

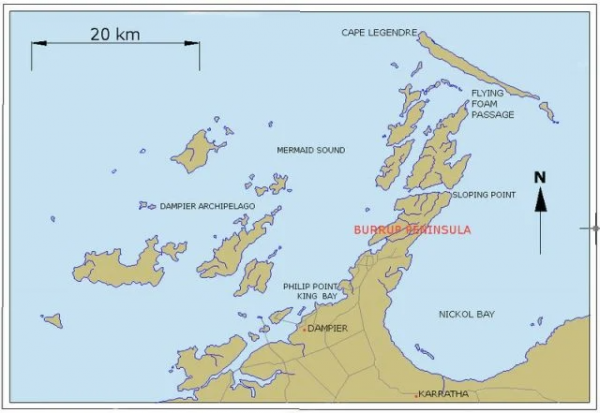

The Juukan Gorge 1 and 2 rock shelter caves were destroyed the metal-mining company Rio Tinto last month. The caves, located in Western Australia, in the Pilbara region, are one of the country’s oldest aboriginal heritage sites, with signs of continuous signs human occupation that predate the last Ice Age, according to a report in the Independent.

Despite the fact that the incident is now being called an ‘incomprehensible mistake,’ it appears that the company knew about the site and its significance at least six years ago.

In 2014, an archaeologist named Michael Slack confirmed that the Juukan 2 cave was unique in the Pilbara area, and rare across Australia as a whole.

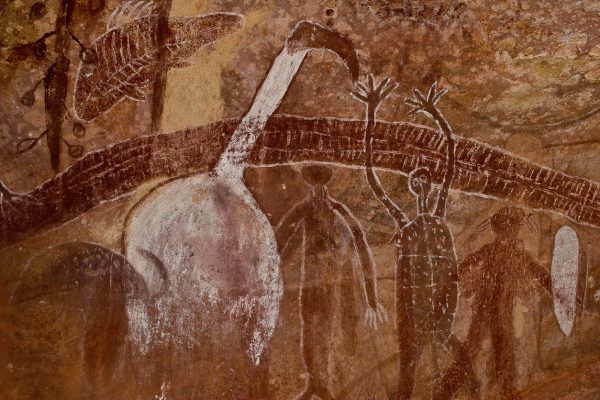

The site held evidence of more than 40,000 years of ongoing human habitation, and contained large numbers of artifacts, including objects made of flaked stone, stone tools, bits of human hair, and an unusually large supply of animal remains.

It also contained sedimentary material with enough of a pollen record that scientists could track thousands of years’ worth of environmental changes.

The Australian Broadcasting Company was given a summary of Slack’s report, which was given both to Rio Tinto and to the Pinikura and Puutu Kunti Kurrama (PKKP) indigenous people six years ago, but was never released to the public.

Slack and his team removed more than 7,000 artifacts from the Cave 2 system in 2014, and his report noted that their findings were of the highest archaeological significance for Australia. Interestingly, the mining company did seem to be aware of the cultural significance of the site.

The year after Slack’s report, they funded a documentary about the site, called Ngurra Minarti, which translates as ‘Our country.’

The documentary included indigenous people of the area taking about their concerns for protecting the region’s remaining cultural sites, including the caves.

The PKKP had reportedly visited the site earlier this month, in hopes of negotiating the stoppage, or at least limitations, on the mining operations, but had been told that the explosives were already in place and couldn’t be removed.

The mining company had been given approval to mine the area in 2013, before Slack’s team made their discoveries and proved the site was of even greater significance than previously believed.

At the time, the appropriate permissions were obtained from the Minister for Aboriginal Affiars, in accordance with a 1972 law which had been written to favor mining companies.

The text of the law says that any activity that could destroy or damage aboriginal site needs to apply for permission through the Aboriginal Cultural Material Committee, which implies that the concerns of the indigenous people are being considered; however, nothing specifies that indigenous people must be part of the committee. Furthermore, the committee’s decisions are final and without appeal.

Rio Tinto has been receiving both domestic and international backlash over the site’s destruction by outraged members of the public.

But has been defending its actions by saying both that it followed the appropriate steps for obtaining permissions and also that the company has worked well with the PKKP on various matters related to aboriginal heritage matters, sometimes modifying operations to protect cultural sites.

In the face of outcry from multiple fronts, including Unesco, from which a spokesperson compared the caves’ destruction to ISIS’s destruction of Palmyra, Chris Salisbury, the iron ore chief executive for the company, eventually apologized.

He called the act a ‘misunderstanding,’ and said that the company took ‘full accountability.’

He said that the company was sorry for the distress it caused, and paid its respects to the PKKP. The company would be working with the PKKP in the future to learn from what happened, and would urgently be reviewing their plans for other sites in the region.

Forty-One Thousand Year Old Tree Tells Of Earth’s Magnetic Reversal

Learning from one’s mistakes is always a good way to go, but, unfortunately, it will do nothing to mitigate the loss the indigenous people have already sustained in the caves’ destruction.