Fukushima: Japan ‘to Release Toxic Water into the Ocean’

Fukushima: Just as the world’s focus turns more acutely than ever to problems with climate change and the environment, setbacks continue plaguing countries around the globe.

First, America pulls out of the Paris Climate Accord. And now, the Japanese government is considering dumping a million or so tons of potentially toxic water into the Pacific Ocean, beginning in 2022.

Just how toxic the water is is up for debate, with arguments falling along predictable lines: environmentalists say any radioactivity is too much in this contaminated water from 2011, while government officials say it will be filtered and cause no consequences to the sea and the marine life within it.

The truth is likely somewhere in the middle, smack in between those two positions.

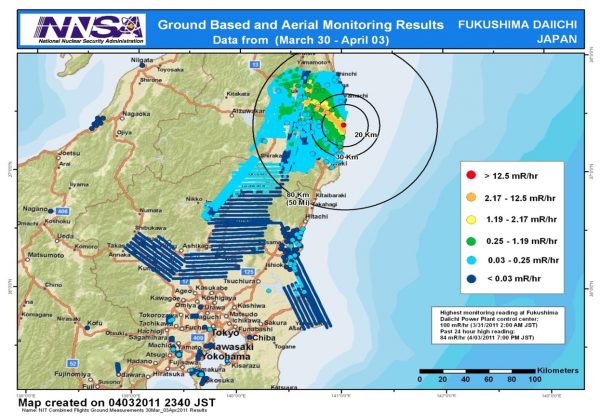

In March of 2011, an enormous earthquake struck the northeastern coast of Japan. As if that event was not devastating enough – it hit nine on the Richter scale – the quake caused a massive tsunami that reached 15 metres.

Approximately 18,500 people either vanished or died, while an additional 160,00 people were forced to abandon their homes. The area was ruined and billions of dollars in compensation was paid by the government to help families and businesses cope with the tragedy.

But another problem arose. Although the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant managed to get through the earthquake relatively unscathed, it did not survive the tsunami. The plant’s nuclear reactor had to be cooled by an incredible amount of water, which in turn became radioactive.

The plant has been abandoned since the disaster, and citizens in the region still suffer trauma from the incident. But an urgent question is: how to dispose of the water safely, with as little damage to the environment as possible? The question has been plaguing Japanese government officials for years now.

The government argues that the filtering process has left the water virtually harmless. But those opposing the dump argue that there is no such thing as a safe amount of radioactivity in water, and that a better solution must be found.

Whichever way the issue is resolved, a decision must be reached soon. The tanks at the plant, and other storage areas on the grounds, are rapidly filling. The water must be dispensed with before the plant can be fully decommissioned.

The disaster at Fukushima is the world’s worst since the events at Chernobyl, in Russia, in 1986.

It has left citizens in the region with deep emotional scars, and the area is littered with empty houses and other reminders of the tragedy. But Japan likely won’t move away from reliance on nuclear energy for some time to come: a recent report by the Ministry of the Economy suggested that the nation will need at least one-fifth of its energy demands to be answered by nuclear power until, at the earliest, 2030.

But officials are considering ways of beginning renewable energy plants, and moving away from coal, nuclear power and other problematic sources of fuel.

One individual told BBC-TV last year that the community endured tremendous pain in the days and years after the incident. “We suffered heavily after the blast,” he recalled, and acknowledged that many are still deeply troubled by what happened.

Today, the question confronting the government is how to safely dispose of all that water, and how to know how much damage it may cause to the ocean once it is released.

Another Article From Us: Go Vegetarian to Save the Planet a New Documentary From Sir David Attenborough Says You Should

Scientists and marine biologists are doing their best to inform officials – and assuage the fears of citizens and environmentalists – but there may be no way of truly knowing the consequences until the water is dumped. And if the results are by some chance catastrophic, it will be by then too late to change course.