Victory For Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Over Dakota Access Pipeline Case

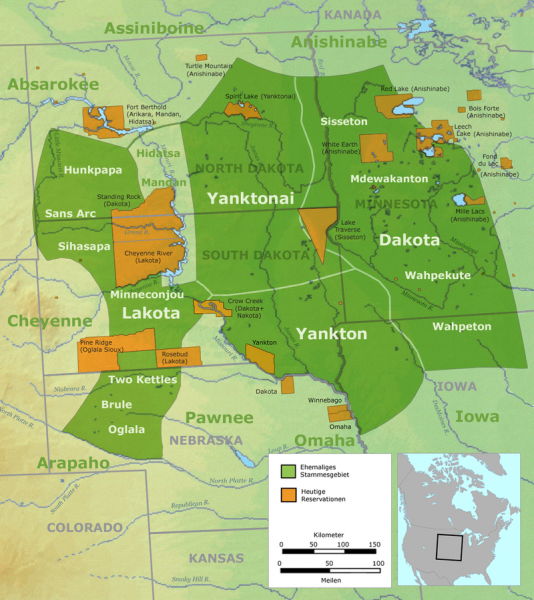

The members of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe that straddles North and South Dakota believed they were never properly consulted nor given the opportunity to conduct independent environmental tests.

When, in January of 2016, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for the Omaha District announced their plan to proceed with putting an oil pipeline under the Missouri River.

They have been fighting the Dakota Access Pipeline ever since. In March of 2020, they finally achieved a victory when a federal judge ordered an in-depth review of the impact on the environment.

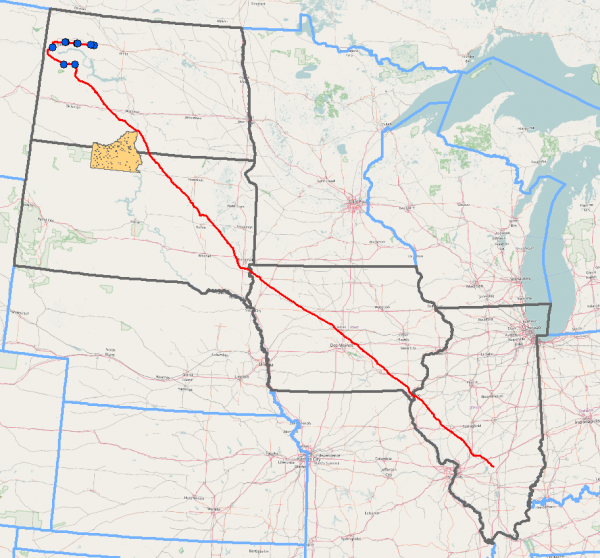

According to Dakota Access Pipeline, the pipeline starts in northwestern North Dakota from the Bakken oil fields and travels through South Dakota and Iowa to get to a station in Patoka, Illinois.

It runs one thousand one hundred and seventy-two miles, is thirty six inches in diameter, and transports five hundred and seventy thousand barrels of oil every day which is almost twenty-four million gallons of oil in US standard measurement. That transforms into over ten million U.S. gallons of gasoline.

The parent company, ©Energy Transfer LP of Dallas, Texas, claims the pipeline is four feet deep in most areas and eighteen inches deeper than the standard requirement for under farmlands.

There are also existing pipelines in the same area including the Northern Border Pipeline built much closer to the surface in 1982.

In January of 2016, The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for the Omaha District invited comments from the public on its published plan to go forward with the pipeline which runs near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation.

By April the Army Corps published their findings that the pipeline and its construction would affect no historic properties even though the Corps’ senior field archaeologist for the project disagreed.

The tribe then asked for an archaeological survey. In July, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers approved the route that crossed the Missouri River at Lake Oahe reservoir on land owned by the Army Corps.

According to NPR, Omaha district commander, Col. John Henderson, remarked, “I have evaluated the anticipated environmental, economic, cultural and social effects and any cumulative effects of the river crossing and found it is not injurious to the public interest.”

So the construction began. A protest camp stayed for months near the construction site. Photographer Larry Trowell told CNN that the camp appeared to grow to around 5000 people throughout the year.

NPR timelines the continued legal battle: In August of 2016, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe brought litigation claiming that the Corps of Engineers had disregarded the National Historic Preservation Act and had failed to satisfactorily discuss the project with tribal leaders.

They were countersued by Dakota Access LLC, a subsidiary of ©Energy Transfer LP for interfering with construction work with protests. It caught the attention of then President Barack Obama who worked with the Corps to negotiate a way that would satisfy both sides.

Throughout November protests continued until sometime in December when the Corps announced it would provide an environmental impact statement and solicit public comments until February regarding if they could place an easement to not only drill under Lake Oahe but also construct high tension electrical towers to electronically monitor the pipelines.

On January 21, 2017, Donald Trump took the office of the Presidency and two days later signed easement approval allowing the Corps to speed up the process.

By February 7th, the Army Corps announced it was not going to complete the environmental impact assessment nor would they entertain comments from the public and began work to go under the lake.

In 2017, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe challenged the validity of the permits in court and lost.

The Army Corps was required to complete their environmental analysis but kept meetings secret from the Tribe. They decided the previous analysis was sufficient and no changes were needed.

The Tribe went back to court and fought for four more years until March of 2020 when New York Times reported that a federal judge ordered a new, in-depth environmental study.

The judge is also requiring the Corps and the tribe to submit briefs about whether or not the pipeline should continue operating during the environmental review.

According to EarthJustice, “The Court found the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers violated the National Environmental Policy Act when it affirmed federal permits for the pipeline originally issued in 2016.

Five Islands Appear In Arctic: Melting Ice Reveals Lands Not Seen Before

The Tough Life of Early US Pioneers

Specifically, the Court found significant unresolved concerns about the potential impacts of oil spills and the likelihood that one could take place.” This validates the complaints of the Tribe since 2016 and opens the case again.