The Brief & Fiery History of the Pony Express

There’s a saying that no matter how fast computers and internet speeds get, they’re not fast enough. Our insatiable desire for speedy communications has pushed technology hard, and engineers work constantly to create faster equipment and develop faster systems of communication.

This lust for speed is nothing new; what’s new is the high speeds at which modern communications take place. The idea of getting messages through quickly has probably existed as long as man has been around. The major empires of the past struggled to get messages through to their farthest outposts, making governing difficult. This problem persisted until electronic communications took over.

One of the times when this lust for speed created a unique solution was in the Old West. Between the California Gold Rush, the Mormon settlement of Utah, and pioneers moving west over the Oregon Trail, the population of the west was growing rapidly. This created a need for faster communications between the east and west coasts. This problem found a temporary solution in the Pony Express.

The Pony Express

The Pony Express only existed for a brief period of eighteen months before electronic communications took over. During its short and fiery career, it delivered mail at what for those days was breathtaking speed. Operating from the end of existing telegraph lines at St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California, it carried messages in about ten days. Compared with eight weeks for mail sent by ship or twenty-four days for mail sent by stagecoach, ten days was incredibly fast. Their fastest delivery time was seven days seventeen hours, carrying President Lincoln’s inaugural address.

The Pony Express was probably the brainchild of California Senator William M. Gwin and B.F. Ficklin, superintendent of the freight company of Russell, Majors and Waddell (although there is some disagreement on this). These visionaries may have stolen the idea from the Mongols, who were the first to use a similar system during the time of Ghengis Khan. In the Mongolian system, a single rider would cover about 300 miles in a day, changing horses every twenty-five miles. Something similar was done in the early 1800s between New York and Boston

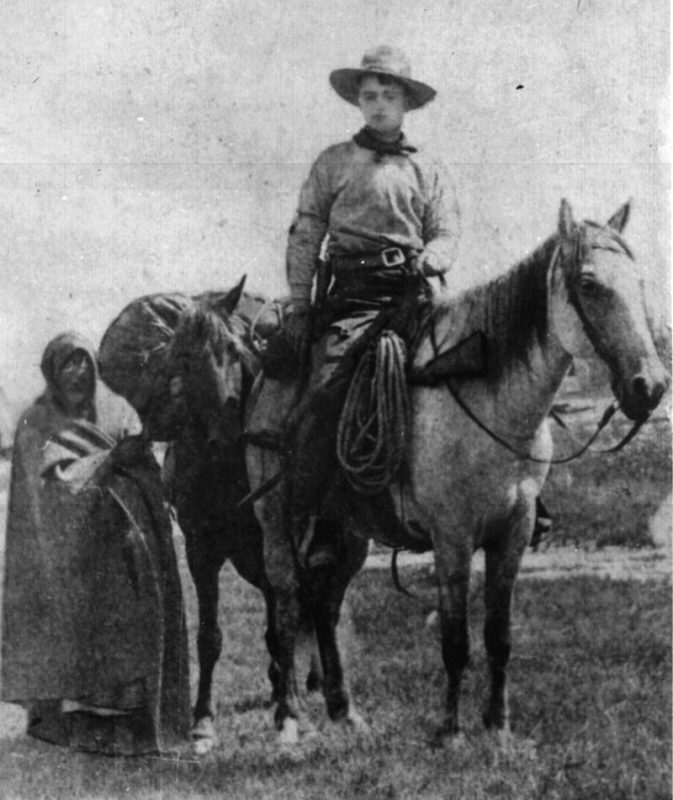

The system used young riders covering roughly 1,900 miles of trail on sturdy quarter horses. Each of the eighty riders covered seventy-five to a hundred miles in a day and changed horses every ten to twelve miles, which allowed them to cover the entire distance with the horses running at a trot or canter rather than a gallop like most people think.

In order to accomplish this, a series of 184 stations were established along the route, each stocked with horses and with a caretaker to care for them. This, not riding, was the most dangerous job in the company, with more than one station overrun and burned out by marauding Indians.

The caretaker would have a well-rested horse ready and saddled when the rider appeared. This allowed the rider to grab the specially-designed saddlebags (called “mochila” after the Spanish word for knapsack) off the saddle, tighten the girth on his new mount, and saddle up – all in less than two minutes. Little time was wasted in making the change, offering the maximum possible time on the trail.

In stations where riders changed, the incoming rider would dismount and throw the mochila to the relief rider, who could set it on his saddle and start riding. This ingeniously designed device was held in place by the rider’s weight, which eliminated the need to tie it down.

The mochila had four padlocked pockets. Three were used for the mail and one for the rider’s timecard. A total of twenty pounds of letters could be carried in those pockets. At a rate of $5 for every ½ ounce, that made the cargo rather precious at $3,200 per load. Amazingly, only one bag was reported lost during the Pony Express’s entire time of operation.

The riders themselves were carefully selected – more for their weight than anything else. No riders could weigh more than 120 pounds, and this limited the load for the horse to 165 pounds. This was necessary to keep the horses from tiring prematurely. Riders received $100 to $150 per month, which was a princely sum in those days considering cowboys earned roughly a dollar a day.

While the riders typically rode a hundred miles per day or less, the record was 380 miles in two days. In May 1860, Robert “Pony Bob” Haslam took off on his scheduled ride. Upon arriving at Buckland Station in Nevada, he found that his relief rider was unable to take over as he was frozen in fear of the Paiute Indians who had been attacking the Pony Express’s stations. Pony Bob grabbed the mochila, mounted his relief’s horse, and continued the run. Arriving at Smith’s Creek, he was able to turn the mochila over to the next relief rider and get a little rest.

But Pony Bob didn’t rest for long because he had to carry the westbound mail back to Buckland Station. By the time he arrived, he had ridden 380 miles in less than forty hours, passing one burned out station along the way.

Destined for Failure

Sadly, the Pony Express was destined for failure from the very beginning. It was an expensive undertaking to operate and never turned a profit, but that wasn’t what caused it to die. Ten weeks after the Pony Express started operations, Congress passed a bill authorizing the Secretary of the Treasury to subsidize the construction of an overland telegraph line running from the Missouri River to the West Coast.

In work much like the building of the transcontinental railway, this was accomplished by the Overland Telegraph Company of California and the Pacific Telegraph Company of Nebraska. While under construction, the Pony Express operated as normal and carried mail and telegrams between the farthest-reaching stations of the telegraph lines. But that could only last for so long.

On October 26, 1861, just eighteen months after the Pony Express’s inaugural ride, the company shut down. Operations actually continued to run for another ten days so that the riders en route could finish their runs; but once those riders had arrived at the ends of the line, the Pony Express ceased to exist.

Yet, during the eighteen months of its existence, the Pony Express earned a legacy in American history. Its riders made a total of 308 complete runs, delivering a total of 34,753 letters in that time. While it failed to meet the primary goal of any business, profitability, it did do a lot to help bring the nation together by operating under extraordinary difficulties in a time when that was necessary.